The stage is a world with a window to look through. The window may be huge or pin-hole tiny. The aperture expands like a camera, only the process is often more organic than mechanical. This is seen many times in ‘the Convert’ as views expand and contract around various themes. ‘The convert’ is a tale of tensions, dichotomies and schisms. It is also a tale of change: people and issues move through states of religion, culture, identity, even from life to death… and back. Almost every action is a metaphor, a powerful allusion or a crypt to untangle. There is an intricate permutation of perspectives as race, colonisation, gender, and religion are looked at through the lens of each other.

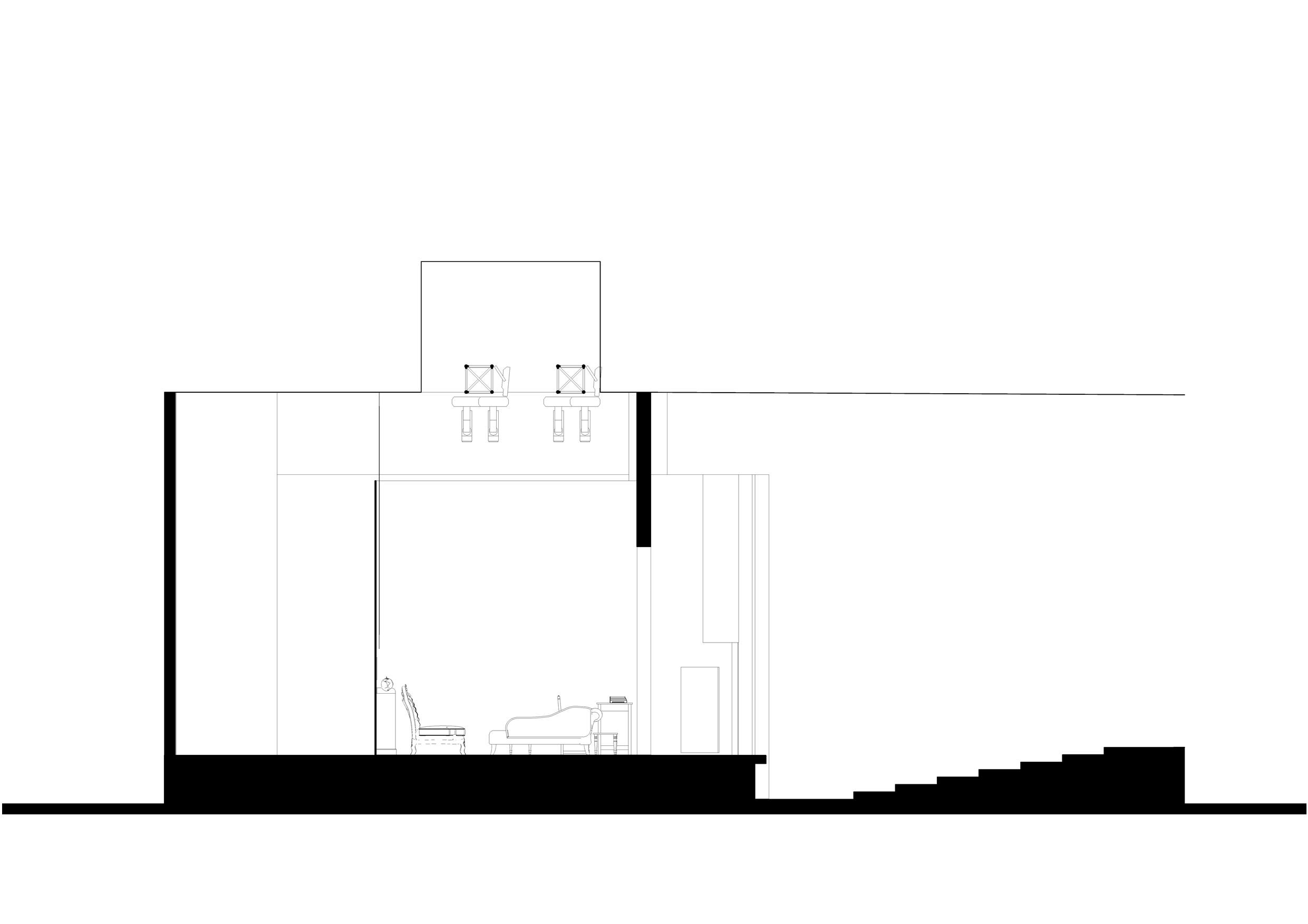

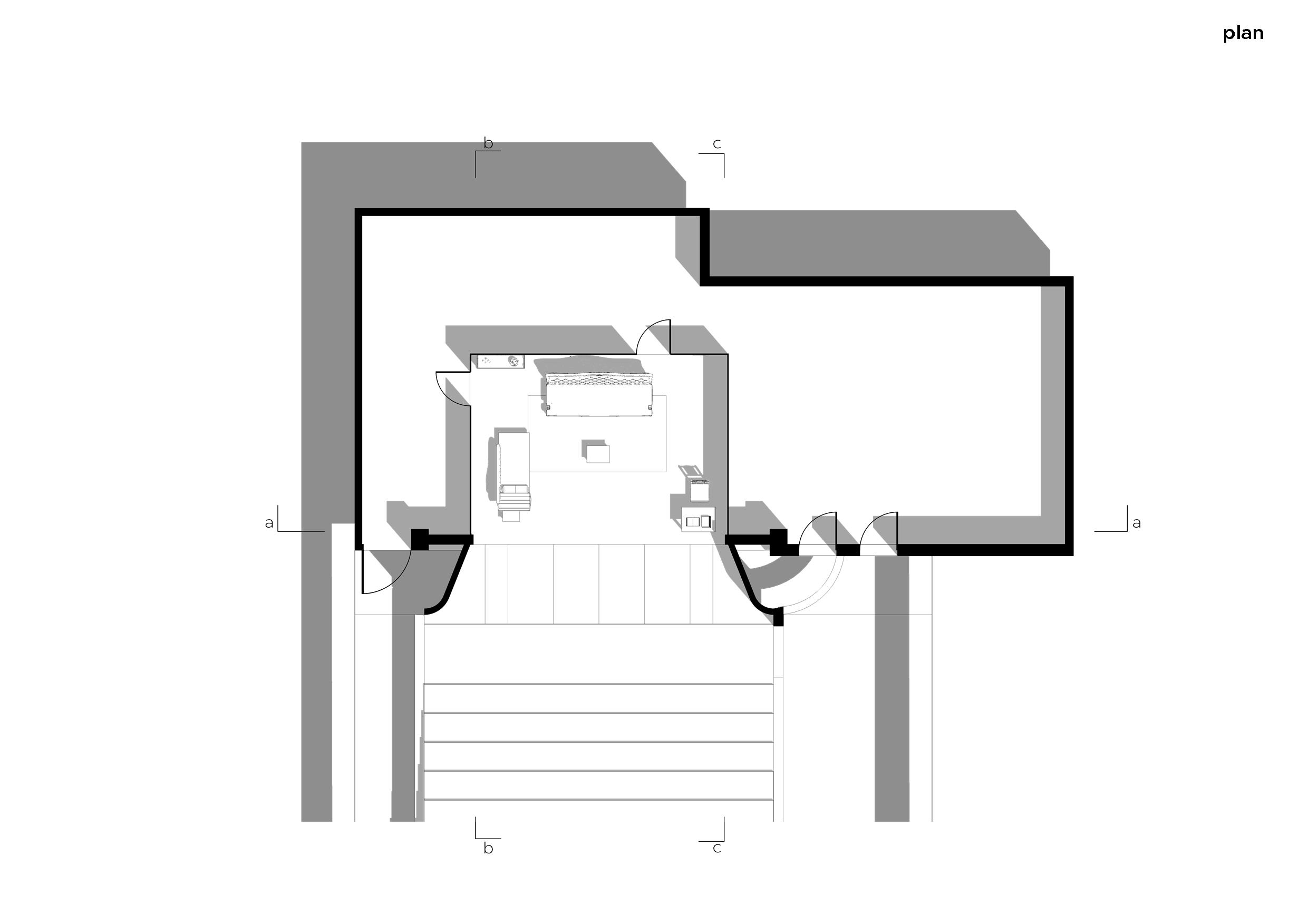

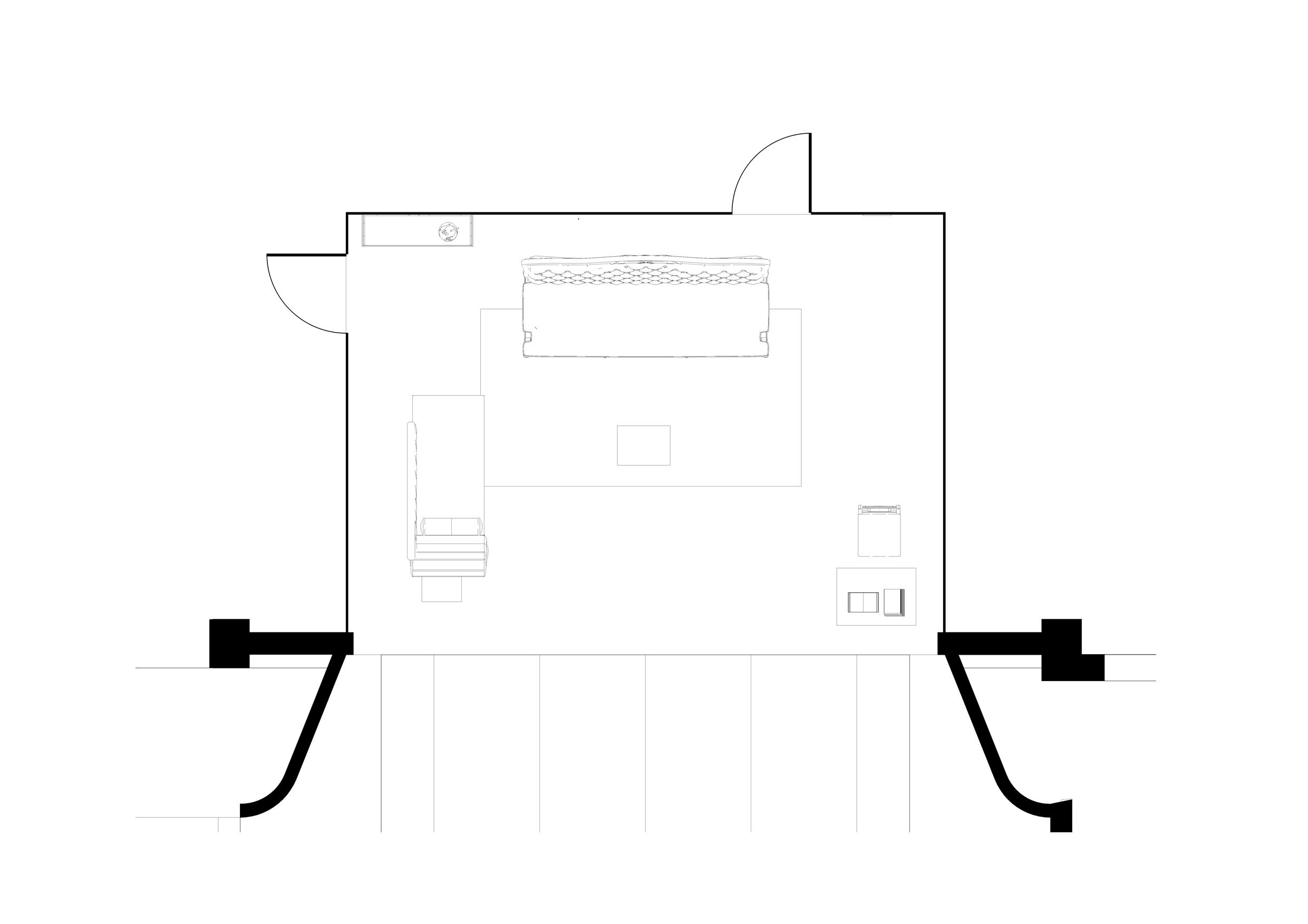

Dealing with the orchestration of a space where this happens can be challenging. One might say it is easy to plan such a space since some brief descriptions are given before or in-between the acts and scenes. The story and the characters, however, engage the space at various levels of depth, using objects, regions and proximities within the set to amplify or mystify messages. This can be noticed in many ways; from the cement floor being engaged to contrast cultures and as a baseline or cradle of life, to the subtle brushings of a Mutsvairo on a surface not sure of its own origin or belonging.

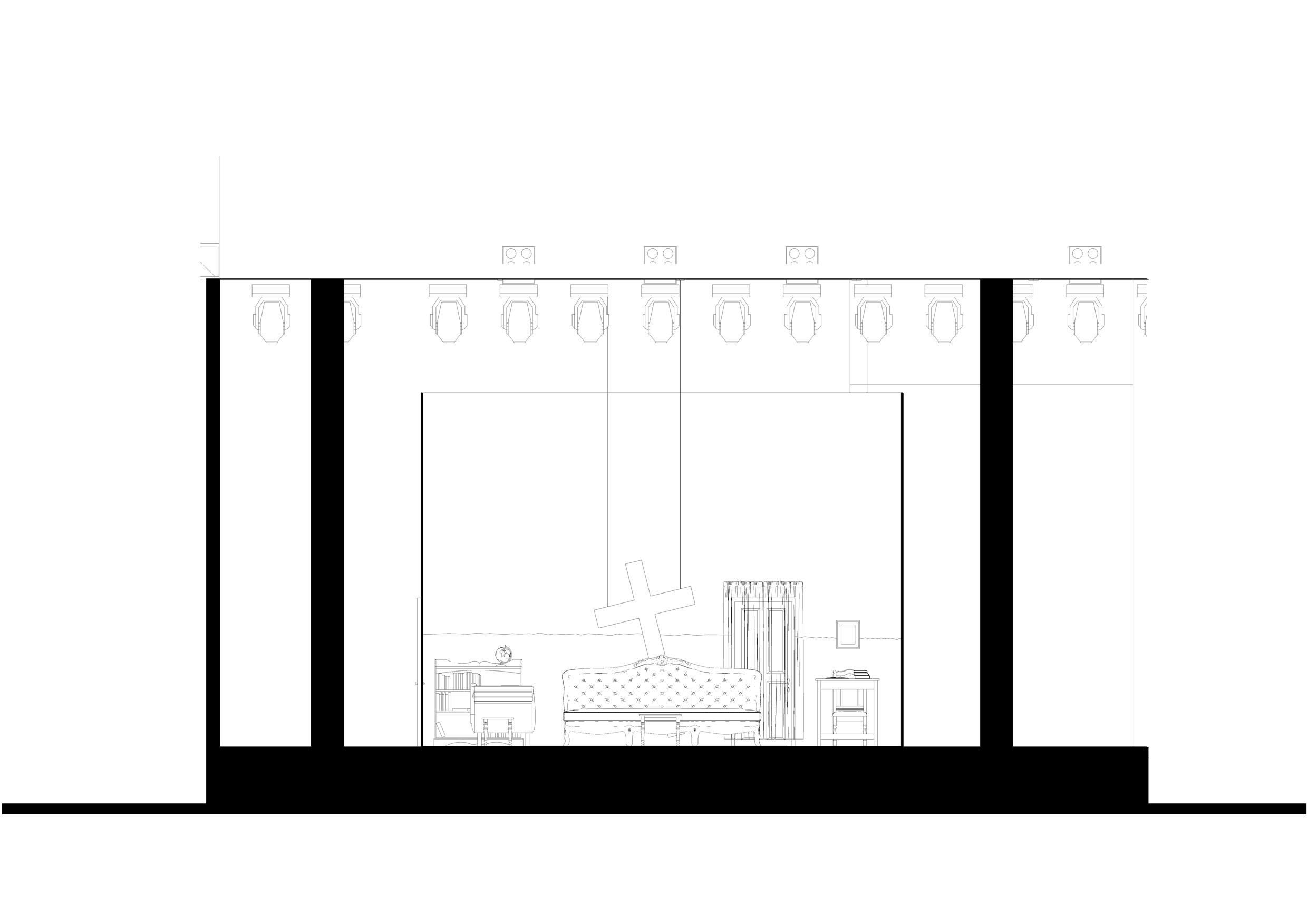

Almost every action is a metaphor, a crypt to untangle. The story is filled with tensions between realities and pseudo-realities, between languages, gods, race, gender and cultures. The stage orchestrated does not attempt to fully stay out of these tensions. It of course, serves as an arena of play for the forces, but is also accentuates the possibilities of their manifestations. The center wall for instance is split in two. One half is a dirty wall and the other half is one decorated with patterns of the period. The tugs between various domains are enhanced and are in constant remembrance throughout the play. The cross is tilted ever so slightly enough to just be visually uncomfortable, which the characters ignore. This pushes the primary argument of religion and colonisation, along with all the ‘luggage’ that comes with it. The cement floor is black with a present absence, save for the threadbare rug in the center of the room. The proximities and hues of the furniture all attempt to amplify not only the plot but the nature of the characters themselves and the issues they deal with.

Many things evolve and change throughout the story; Not only the girl changes—who becomes Esta, then becomes Jekesai Wekwa Chiyangwa Murumbira. Alongside with the light, sound and the souls of the characters projected, the space is designed to not only accommodate these changes and forces…but to embody them.